A former CEO of Girl Scouts of the U.S.A. defines leadership and discusses her time with management expert Peter Drucker and his influence on the Scouts.

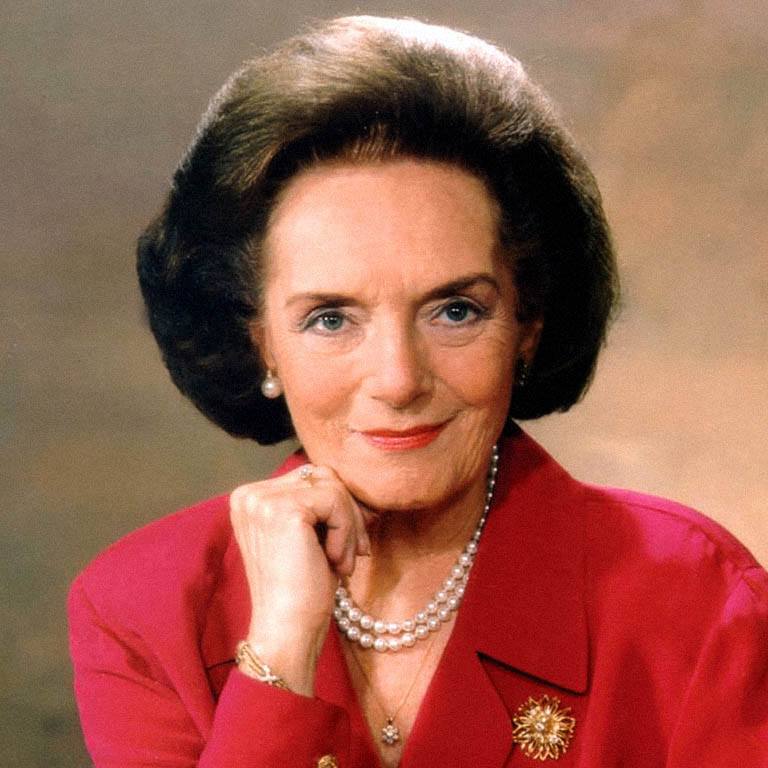

Frances Hesselbein

Featured Leadership Topics

Define Your Vision

“Everything begins with mission. Everything is centered by mission. Mission is solely, why do we do what we do? A reason for being.”

Description of the video:

Scarpino: I know you need to take a call in a few minutes. So I want to ask you a question related to Peter Drucker’s first visit to the Girl Scouts.

Hesselbein: Yes.

Scarpino: And then I’ll turn these things off. So when I talked to you last time, when you weren’t feeling well, you mentioned that when Peter Drucker came to New York for the first time to meet with you and with the Girl Scout staff and so forth, that one of the things that he said was, he said—and I’m quoting you now—you said Peter Drucker said you do not appreciate the significance of the work you do for we live in a society that pretends to care about its children but does not.

Hesselbein: Care about its children and it does not.

Scarpino: Right. And so you were taken back by that.

Hesselbein: Shocked.

Scarpino: And then a number of years later you called him up and asked him did he still feel that way, and he said yes.

Hesselbein: No, he said in a very sad voice, Frances has anything changed? No, of course not.

Scarpino: So, do you agree?

Hesselbein: Yes.

Scarpino: That ours is a society that pretends to care for children but does not?

Hesselbein: Yes.

Scarpino: And how, as somebody who has spent her entire life learning to be a leader and training other people to be leaders, how do you see that happening? How is it that we say we care about our children but we don’t? What evidence do you have for that?

Hesselbein: We will go to 10 cities, visit the schools, how many children receive a high school diploma. You have some cities where half of people sent do not. I think New York has improved. I think now 70, we graduate 70, but a few years ago when I was speaking we were one out of two. When we look at the percentage of children in our country, find the newest percentages and the millions and millions and millions of children and the high percentages of black and Hispanic and poor children who do not get a high school diploma, no diploma, no hope, no job, no future, and you look at the youth prisons and the teenagers incarcerated and the situations there, if we really cared, if we really cared about all of our children, education would be available and we would see that the poorest child had that opportunity.

Scarpino: How do you think that our society reached a point where we tell each other we care about our children but in your opinion we do not?

Hesselbein: Because these are our invisible children. Do you—how many children do you know who sleep in homeless shelters get up in the morning and go to high school?

Scarpino: I’m the wrong person to ask because some of my students do service learning projects and work with those children, so I know there are a lot in Indianapolis who live like that.

Hesselbein: All right. But you know, but you know how it is. They are. Tell Doug to come in.

Scarpino: Do you want me to hit pause and shut this off?

Hesselbein: Yes, and this will just be a few minutes then you can come.

Scarpino: All right, let’s make sure that we have these things turned off and I’ll get out of here.

[short break]

Scarpino: All right, it should be back on again. Let me get myself re-oriented here. Okay, we were, when we took a break we were talking about the first time that Peter Drucker came to the Girl Scouts and he, among a number of things, mentioned that a society that pretends to care for children but does not.

Hesselbein: Yes.

Scarpino: And we, I was asking you, your point of view on that, and asked you how do you think we got to the point where we say we care but we don’t.

Hesselbein: I think we forgot who we were. I look at small countries in other parts of the world and they’re number one in something that’s important, and we’re 28. I don’t know. We focused elsewhere and somehow the education of all of our children has to become a passionate focus of the whole country. I believe that since the beginning of our country there have been two institutions that have sustained a democracy. One is the United States Army and the other is public education. Today the Army is stretched but strong. For public education the house is on fire. You cannot have a schoolhouse where the children do not have books, where they do not have a library. We’re now cutting teacher salary, raising class sizes, when we know what size class is best for children. There’s a long list. I don’t know how we got there. but being there is not good enough for most of us and we need to all battle to get us back to the point where the education of all of our children is a priority.

Scarpino: How do you think we ended up as a society in a place where we spend money on one of the institutions that you value, that is the military, and we cut the budget of the other institution that you value, which is public education.

Hesselbein: I don’t see it that way at all because we are not overspending on the military, but if you look at everything else we spend money for and where we are not investing, we need to take a tough look at what’s our priorities in spending and projects and focus. And we focus on what builds strong families, strong communities, with civil discourse and civil society. How did we ever get to this point where we speak to one another in such a shocking way? Civil discourse, civil society.

Scarpino: In addition to civil discourse and civil society, if you could pick one or two things to work on, what would you pick?

Hesselbein: Strengthening the public schools of our country. I would pick one.

Scarpino: One school.

Hesselbein: One sector, one issue. I think that’s where the house is on fire.

Scarpino: Do you think that the situation with America’s children represents a crisis of leadership or a failure of leadership?

Hesselbein: Both. Both, and the lack of caring. If we really cared about our children would we have schools without libraries or textbooks? Of course not.

Scarpino: You have a picture on your wall of some young high school-age looking children that I believe went to a high school in the Bronx, and were in a situation where they didn’t have books or a library.

Hesselbein: South Bronx, an alternative high school for young people at risk where I was principal for a day and worked with them for the next eight years. The student council, when I met with them after that first day, principal for a day, just observing, met with 10 members of the student council, and I said when we meet at three o’clock, you will tell me your greatest needs.

We met at three and a young president, Joe, stood up and said Mrs. Hesselbein, our greatest need is a library. We don’t have one and wouldn’t it be wonderful for all the kids if we could have a library? Number two greatest need: textbooks. They had seven subjects. And he said, wouldn’t it be wonderful if all the kids could have a textbook. Number three, I’d been talking with the whole student body and teachers about it and he got the message. He said could you find—it was about all of us working to make it a better place—he said could you find a mentor who would help us move beyond the walls, go out into South Bronx with a project that would make it a better place for everyone? Now, those young people, 90% poverty level, 90% black, or Hispanic had this beautiful vision of what it could be. They had never graduated a class from that high school. The next June we graduated nine members of student council in the 52 group of graduates. Number 10 went to the Air Force. Loads more, college scholarships. All they needed was a library and textbooks.

Scarpino: Are you still in touch with that school?

Hesselbein: It has now closed.

Scarpino: If the situation with the children is a crisis or a failure of leadership what does the Leader to Leader Institute do to address that crisis or that failure?

Hesselbein: Well, I travel every week speaking somewhere, and it’s always in my speeches. In leadership dialogues I talk about it because I really believe that the two institutions that are to save the democracy have been public education and United States Army, and I keep testing my thesis and I believe it more passionately every day. So wherever I go I talk about it.

Shortly after that, after the opening of the library, two young men took me aside—they were young African-American students—and they, very quietly away from everyone, they said Mrs. Hesselbein do you think we could have a couple of books written by people who look like us, you know, people who look us like write books too. And I said, some of the greatest, of course. A friend gave me the definitive list of books by African-American authors but said if you buy all of them it would be $6000. So I talked to a friend and I said I’d like to just buy all of them, and he said absolutely and I said well if you could find half of it, I’ll find half. He called me back and he said forget about your half, our company is buying all of them. So we had a party and those young men who came every day to the library after school to help as library helpers, they had the books on the shelves. Most of them, the cover had the photograph. They had the cover out. You’ve never seen such a beautiful prize. It doesn’t take much. We’re not talking about billions. But where we are, on the ground, where the kids are, what can we do?

Understand Leadership

“Leadership is a matter of how to be, not how to do.”

Description of the video:

Scarpino: I know you need to take a call in a few minutes. So I want to ask you a question related to Peter Drucker’s first visit to the Girl Scouts.

Hesselbein: Yes.

Scarpino: And then I’ll turn these things off. So when I talked to you last time, when you weren’t feeling well, you mentioned that when Peter Drucker came to New York for the first time to meet with you and with the Girl Scout staff and so forth, that one of the things that he said was, he said—and I’m quoting you now—you said Peter Drucker said you do not appreciate the significance of the work you do for we live in a society that pretends to care about its children but does not.

Hesselbein: Care about its children and it does not.

Scarpino: Right. And so you were taken back by that.

Hesselbein: Shocked.

Scarpino: And then a number of years later you called him up and asked him did he still feel that way, and he said yes.

Hesselbein: No, he said in a very sad voice, Frances has anything changed? No, of course not.

Scarpino: So, do you agree?

Hesselbein: Yes.

Scarpino: That ours is a society that pretends to care for children but does not?

Hesselbein: Yes.

Scarpino: And how, as somebody who has spent her entire life learning to be a leader and training other people to be leaders, how do you see that happening? How is it that we say we care about our children but we don’t? What evidence do you have for that?

Hesselbein: We will go to 10 cities, visit the schools, how many children receive a high school diploma. You have some cities where half of people sent do not. I think New York has improved. I think now 70, we graduate 70, but a few years ago when I was speaking we were one out of two. When we look at the percentage of children in our country, find the newest percentages and the millions and millions and millions of children and the high percentages of black and Hispanic and poor children who do not get a high school diploma, no diploma, no hope, no job, no future, and you look at the youth prisons and the teenagers incarcerated and the situations there, if we really cared, if we really cared about all of our children, education would be available and we would see that the poorest child had that opportunity.

Scarpino: How do you think that our society reached a point where we tell each other we care about our children but in your opinion we do not?

Hesselbein: Because these are our invisible children. Do you—how many children do you know who sleep in homeless shelters get up in the morning and go to high school?

Scarpino: I’m the wrong person to ask because some of my students do service learning projects and work with those children, so I know there are a lot in Indianapolis who live like that.

Hesselbein: All right. But you know, but you know how it is. They are. Tell Doug to come in.

Scarpino: Do you want me to hit pause and shut this off?

Hesselbein: Yes, and this will just be a few minutes then you can come.

Scarpino: All right, let’s make sure that we have these things turned off and I’ll get out of here.

[short break]

Scarpino: All right, it should be back on again. Let me get myself re-oriented here. Okay, we were, when we took a break we were talking about the first time that Peter Drucker came to the Girl Scouts and he, among a number of things, mentioned that a society that pretends to care for children but does not.

Hesselbein: Yes.

Scarpino: And we, I was asking you, your point of view on that, and asked you how do you think we got to the point where we say we care but we don’t.

Hesselbein: I think we forgot who we were. I look at small countries in other parts of the world and they’re number one in something that’s important, and we’re 28. I don’t know. We focused elsewhere and somehow the education of all of our children has to become a passionate focus of the whole country. I believe that since the beginning of our country there have been two institutions that have sustained a democracy. One is the United States Army and the other is public education. Today the Army is stretched but strong. For public education the house is on fire. You cannot have a schoolhouse where the children do not have books, where they do not have a library. We’re now cutting teacher salary, raising class sizes, when we know what size class is best for children. There’s a long list. I don’t know how we got there. but being there is not good enough for most of us and we need to all battle to get us back to the point where the education of all of our children is a priority.

Scarpino: How do you think we ended up as a society in a place where we spend money on one of the institutions that you value, that is the military, and we cut the budget of the other institution that you value, which is public education.

Hesselbein: I don’t see it that way at all because we are not overspending on the military, but if you look at everything else we spend money for and where we are not investing, we need to take a tough look at what’s our priorities in spending and projects and focus. And we focus on what builds strong families, strong communities, with civil discourse and civil society. How did we ever get to this point where we speak to one another in such a shocking way? Civil discourse, civil society.

Scarpino: In addition to civil discourse and civil society, if you could pick one or two things to work on, what would you pick?

Hesselbein: Strengthening the public schools of our country. I would pick one.

Scarpino: One school.

Hesselbein: One sector, one issue. I think that’s where the house is on fire.

Scarpino: Do you think that the situation with America’s children represents a crisis of leadership or a failure of leadership?

Hesselbein: Both. Both, and the lack of caring. If we really cared about our children would we have schools without libraries or textbooks? Of course not.

Scarpino: You have a picture on your wall of some young high school-age looking children that I believe went to a high school in the Bronx, and were in a situation where they didn’t have books or a library.

Hesselbein: South Bronx, an alternative high school for young people at risk where I was principal for a day and worked with them for the next eight years. The student council, when I met with them after that first day, principal for a day, just observing, met with 10 members of the student council, and I said when we meet at three o’clock, you will tell me your greatest needs.

We met at three and a young president, Joe, stood up and said Mrs. Hesselbein, our greatest need is a library. We don’t have one and wouldn’t it be wonderful for all the kids if we could have a library? Number two greatest need: textbooks. They had seven subjects. And he said, wouldn’t it be wonderful if all the kids could have a textbook. Number three, I’d been talking with the whole student body and teachers about it and he got the message. He said could you find—it was about all of us working to make it a better place—he said could you find a mentor who would help us move beyond the walls, go out into South Bronx with a project that would make it a better place for everyone? Now, those young people, 90% poverty level, 90% black, or Hispanic had this beautiful vision of what it could be. They had never graduated a class from that high school. The next June we graduated nine members of student council in the 52 group of graduates. Number 10 went to the Air Force. Loads more, college scholarships. All they needed was a library and textbooks.

Scarpino: Are you still in touch with that school?

Hesselbein: It has now closed.

Scarpino: If the situation with the children is a crisis or a failure of leadership what does the Leader to Leader Institute do to address that crisis or that failure?

Hesselbein: Well, I travel every week speaking somewhere, and it’s always in my speeches. In leadership dialogues I talk about it because I really believe that the two institutions that are to save the democracy have been public education and United States Army, and I keep testing my thesis and I believe it more passionately every day. So wherever I go I talk about it.

Shortly after that, after the opening of the library, two young men took me aside—they were young African-American students—and they, very quietly away from everyone, they said Mrs. Hesselbein do you think we could have a couple of books written by people who look like us, you know, people who look us like write books too. And I said, some of the greatest, of course. A friend gave me the definitive list of books by African-American authors but said if you buy all of them it would be $6000. So I talked to a friend and I said I’d like to just buy all of them, and he said absolutely and I said well if you could find half of it, I’ll find half. He called me back and he said forget about your half, our company is buying all of them. So we had a party and those young men who came every day to the library after school to help as library helpers, they had the books on the shelves. Most of them, the cover had the photograph. They had the cover out. You’ve never seen such a beautiful prize. It doesn’t take much. We’re not talking about billions. But where we are, on the ground, where the kids are, what can we do?

Inspire Followership

“[My father] and my grandmother had the greatest impact upon my life and my work.”

Description of the video:

Scarpino: I know you need to take a call in a few minutes. So I want to ask you a question related to Peter Drucker’s first visit to the Girl Scouts.

Hesselbein: Yes.

Scarpino: And then I’ll turn these things off. So when I talked to you last time, when you weren’t feeling well, you mentioned that when Peter Drucker came to New York for the first time to meet with you and with the Girl Scout staff and so forth, that one of the things that he said was, he said—and I’m quoting you now—you said Peter Drucker said you do not appreciate the significance of the work you do for we live in a society that pretends to care about its children but does not.

Hesselbein: Care about its children and it does not.

Scarpino: Right. And so you were taken back by that.

Hesselbein: Shocked.

Scarpino: And then a number of years later you called him up and asked him did he still feel that way, and he said yes.

Hesselbein: No, he said in a very sad voice, Frances has anything changed? No, of course not.

Scarpino: So, do you agree?

Hesselbein: Yes.

Scarpino: That ours is a society that pretends to care for children but does not?

Hesselbein: Yes.

Scarpino: And how, as somebody who has spent her entire life learning to be a leader and training other people to be leaders, how do you see that happening? How is it that we say we care about our children but we don’t? What evidence do you have for that?

Hesselbein: We will go to 10 cities, visit the schools, how many children receive a high school diploma. You have some cities where half of people sent do not. I think New York has improved. I think now 70, we graduate 70, but a few years ago when I was speaking we were one out of two. When we look at the percentage of children in our country, find the newest percentages and the millions and millions and millions of children and the high percentages of black and Hispanic and poor children who do not get a high school diploma, no diploma, no hope, no job, no future, and you look at the youth prisons and the teenagers incarcerated and the situations there, if we really cared, if we really cared about all of our children, education would be available and we would see that the poorest child had that opportunity.

Scarpino: How do you think that our society reached a point where we tell each other we care about our children but in your opinion we do not?

Hesselbein: Because these are our invisible children. Do you—how many children do you know who sleep in homeless shelters get up in the morning and go to high school?

Scarpino: I’m the wrong person to ask because some of my students do service learning projects and work with those children, so I know there are a lot in Indianapolis who live like that.

Hesselbein: All right. But you know, but you know how it is. They are. Tell Doug to come in.

Scarpino: Do you want me to hit pause and shut this off?

Hesselbein: Yes, and this will just be a few minutes then you can come.

Scarpino: All right, let’s make sure that we have these things turned off and I’ll get out of here.

[short break]

Scarpino: All right, it should be back on again. Let me get myself re-oriented here. Okay, we were, when we took a break we were talking about the first time that Peter Drucker came to the Girl Scouts and he, among a number of things, mentioned that a society that pretends to care for children but does not.

Hesselbein: Yes.

Scarpino: And we, I was asking you, your point of view on that, and asked you how do you think we got to the point where we say we care but we don’t.

Hesselbein: I think we forgot who we were. I look at small countries in other parts of the world and they’re number one in something that’s important, and we’re 28. I don’t know. We focused elsewhere and somehow the education of all of our children has to become a passionate focus of the whole country. I believe that since the beginning of our country there have been two institutions that have sustained a democracy. One is the United States Army and the other is public education. Today the Army is stretched but strong. For public education the house is on fire. You cannot have a schoolhouse where the children do not have books, where they do not have a library. We’re now cutting teacher salary, raising class sizes, when we know what size class is best for children. There’s a long list. I don’t know how we got there. but being there is not good enough for most of us and we need to all battle to get us back to the point where the education of all of our children is a priority.

Scarpino: How do you think we ended up as a society in a place where we spend money on one of the institutions that you value, that is the military, and we cut the budget of the other institution that you value, which is public education.

Hesselbein: I don’t see it that way at all because we are not overspending on the military, but if you look at everything else we spend money for and where we are not investing, we need to take a tough look at what’s our priorities in spending and projects and focus. And we focus on what builds strong families, strong communities, with civil discourse and civil society. How did we ever get to this point where we speak to one another in such a shocking way? Civil discourse, civil society.

Scarpino: In addition to civil discourse and civil society, if you could pick one or two things to work on, what would you pick?

Hesselbein: Strengthening the public schools of our country. I would pick one.

Scarpino: One school.

Hesselbein: One sector, one issue. I think that’s where the house is on fire.

Scarpino: Do you think that the situation with America’s children represents a crisis of leadership or a failure of leadership?

Hesselbein: Both. Both, and the lack of caring. If we really cared about our children would we have schools without libraries or textbooks? Of course not.

Scarpino: You have a picture on your wall of some young high school-age looking children that I believe went to a high school in the Bronx, and were in a situation where they didn’t have books or a library.

Hesselbein: South Bronx, an alternative high school for young people at risk where I was principal for a day and worked with them for the next eight years. The student council, when I met with them after that first day, principal for a day, just observing, met with 10 members of the student council, and I said when we meet at three o’clock, you will tell me your greatest needs.

We met at three and a young president, Joe, stood up and said Mrs. Hesselbein, our greatest need is a library. We don’t have one and wouldn’t it be wonderful for all the kids if we could have a library? Number two greatest need: textbooks. They had seven subjects. And he said, wouldn’t it be wonderful if all the kids could have a textbook. Number three, I’d been talking with the whole student body and teachers about it and he got the message. He said could you find—it was about all of us working to make it a better place—he said could you find a mentor who would help us move beyond the walls, go out into South Bronx with a project that would make it a better place for everyone? Now, those young people, 90% poverty level, 90% black, or Hispanic had this beautiful vision of what it could be. They had never graduated a class from that high school. The next June we graduated nine members of student council in the 52 group of graduates. Number 10 went to the Air Force. Loads more, college scholarships. All they needed was a library and textbooks.

Scarpino: Are you still in touch with that school?

Hesselbein: It has now closed.

Scarpino: If the situation with the children is a crisis or a failure of leadership what does the Leader to Leader Institute do to address that crisis or that failure?

Hesselbein: Well, I travel every week speaking somewhere, and it’s always in my speeches. In leadership dialogues I talk about it because I really believe that the two institutions that are to save the democracy have been public education and United States Army, and I keep testing my thesis and I believe it more passionately every day. So wherever I go I talk about it.

Shortly after that, after the opening of the library, two young men took me aside—they were young African-American students—and they, very quietly away from everyone, they said Mrs. Hesselbein do you think we could have a couple of books written by people who look like us, you know, people who look us like write books too. And I said, some of the greatest, of course. A friend gave me the definitive list of books by African-American authors but said if you buy all of them it would be $6000. So I talked to a friend and I said I’d like to just buy all of them, and he said absolutely and I said well if you could find half of it, I’ll find half. He called me back and he said forget about your half, our company is buying all of them. So we had a party and those young men who came every day to the library after school to help as library helpers, they had the books on the shelves. Most of them, the cover had the photograph. They had the cover out. You’ve never seen such a beautiful prize. It doesn’t take much. We’re not talking about billions. But where we are, on the ground, where the kids are, what can we do?

Storytelling

“[I]f we really cared about all of our children, education would be available and we would see that the poorest child had that opportunity.”

Description of the video:

Scarpino: I know you need to take a call in a few minutes. So I want to ask you a question related to Peter Drucker’s first visit to the Girl Scouts.

Hesselbein: Yes.

Scarpino: And then I’ll turn these things off. So when I talked to you last time, when you weren’t feeling well, you mentioned that when Peter Drucker came to New York for the first time to meet with you and with the Girl Scout staff and so forth, that one of the things that he said was, he said—and I’m quoting you now—you said Peter Drucker said you do not appreciate the significance of the work you do for we live in a society that pretends to care about its children but does not.

Hesselbein: Care about its children and it does not.

Scarpino: Right. And so you were taken back by that.

Hesselbein: Shocked.

Scarpino: And then a number of years later you called him up and asked him did he still feel that way, and he said yes.

Hesselbein: No, he said in a very sad voice, Frances has anything changed? No, of course not.

Scarpino: So, do you agree?

Hesselbein: Yes.

Scarpino: That ours is a society that pretends to care for children but does not?

Hesselbein: Yes.

Scarpino: And how, as somebody who has spent her entire life learning to be a leader and training other people to be leaders, how do you see that happening? How is it that we say we care about our children but we don’t? What evidence do you have for that?

Hesselbein: We will go to 10 cities, visit the schools, how many children receive a high school diploma. You have some cities where half of people sent do not. I think New York has improved. I think now 70, we graduate 70, but a few years ago when I was speaking we were one out of two. When we look at the percentage of children in our country, find the newest percentages and the millions and millions and millions of children and the high percentages of black and Hispanic and poor children who do not get a high school diploma, no diploma, no hope, no job, no future, and you look at the youth prisons and the teenagers incarcerated and the situations there, if we really cared, if we really cared about all of our children, education would be available and we would see that the poorest child had that opportunity.

Scarpino: How do you think that our society reached a point where we tell each other we care about our children but in your opinion we do not?

Hesselbein: Because these are our invisible children. Do you—how many children do you know who sleep in homeless shelters get up in the morning and go to high school?

Scarpino: I’m the wrong person to ask because some of my students do service learning projects and work with those children, so I know there are a lot in Indianapolis who live like that.

Hesselbein: All right. But you know, but you know how it is. They are. Tell Doug to come in.

Scarpino: Do you want me to hit pause and shut this off?

Hesselbein: Yes, and this will just be a few minutes then you can come.

Scarpino: All right, let’s make sure that we have these things turned off and I’ll get out of here.

[short break]

Scarpino: All right, it should be back on again. Let me get myself re-oriented here. Okay, we were, when we took a break we were talking about the first time that Peter Drucker came to the Girl Scouts and he, among a number of things, mentioned that a society that pretends to care for children but does not.

Hesselbein: Yes.

Scarpino: And we, I was asking you, your point of view on that, and asked you how do you think we got to the point where we say we care but we don’t.

Hesselbein: I think we forgot who we were. I look at small countries in other parts of the world and they’re number one in something that’s important, and we’re 28. I don’t know. We focused elsewhere and somehow the education of all of our children has to become a passionate focus of the whole country. I believe that since the beginning of our country there have been two institutions that have sustained a democracy. One is the United States Army and the other is public education. Today the Army is stretched but strong. For public education the house is on fire. You cannot have a schoolhouse where the children do not have books, where they do not have a library. We’re now cutting teacher salary, raising class sizes, when we know what size class is best for children. There’s a long list. I don’t know how we got there. but being there is not good enough for most of us and we need to all battle to get us back to the point where the education of all of our children is a priority.

Scarpino: How do you think we ended up as a society in a place where we spend money on one of the institutions that you value, that is the military, and we cut the budget of the other institution that you value, which is public education.

Hesselbein: I don’t see it that way at all because we are not overspending on the military, but if you look at everything else we spend money for and where we are not investing, we need to take a tough look at what’s our priorities in spending and projects and focus. And we focus on what builds strong families, strong communities, with civil discourse and civil society. How did we ever get to this point where we speak to one another in such a shocking way? Civil discourse, civil society.

Scarpino: In addition to civil discourse and civil society, if you could pick one or two things to work on, what would you pick?

Hesselbein: Strengthening the public schools of our country. I would pick one.

Scarpino: One school.

Hesselbein: One sector, one issue. I think that’s where the house is on fire.

Scarpino: Do you think that the situation with America’s children represents a crisis of leadership or a failure of leadership?

Hesselbein: Both. Both, and the lack of caring. If we really cared about our children would we have schools without libraries or textbooks? Of course not.

Scarpino: You have a picture on your wall of some young high school-age looking children that I believe went to a high school in the Bronx, and were in a situation where they didn’t have books or a library.

Hesselbein: South Bronx, an alternative high school for young people at risk where I was principal for a day and worked with them for the next eight years. The student council, when I met with them after that first day, principal for a day, just observing, met with 10 members of the student council, and I said when we meet at three o’clock, you will tell me your greatest needs.

We met at three and a young president, Joe, stood up and said Mrs. Hesselbein, our greatest need is a library. We don’t have one and wouldn’t it be wonderful for all the kids if we could have a library? Number two greatest need: textbooks. They had seven subjects. And he said, wouldn’t it be wonderful if all the kids could have a textbook. Number three, I’d been talking with the whole student body and teachers about it and he got the message. He said could you find—it was about all of us working to make it a better place—he said could you find a mentor who would help us move beyond the walls, go out into South Bronx with a project that would make it a better place for everyone? Now, those young people, 90% poverty level, 90% black, or Hispanic had this beautiful vision of what it could be. They had never graduated a class from that high school. The next June we graduated nine members of student council in the 52 group of graduates. Number 10 went to the Air Force. Loads more, college scholarships. All they needed was a library and textbooks.

Scarpino: Are you still in touch with that school?

Hesselbein: It has now closed.

Scarpino: If the situation with the children is a crisis or a failure of leadership what does the Leader to Leader Institute do to address that crisis or that failure?

Hesselbein: Well, I travel every week speaking somewhere, and it’s always in my speeches. In leadership dialogues I talk about it because I really believe that the two institutions that are to save the democracy have been public education and United States Army, and I keep testing my thesis and I believe it more passionately every day. So wherever I go I talk about it.

Shortly after that, after the opening of the library, two young men took me aside—they were young African-American students—and they, very quietly away from everyone, they said Mrs. Hesselbein do you think we could have a couple of books written by people who look like us, you know, people who look us like write books too. And I said, some of the greatest, of course. A friend gave me the definitive list of books by African-American authors but said if you buy all of them it would be $6000. So I talked to a friend and I said I’d like to just buy all of them, and he said absolutely and I said well if you could find half of it, I’ll find half. He called me back and he said forget about your half, our company is buying all of them. So we had a party and those young men who came every day to the library after school to help as library helpers, they had the books on the shelves. Most of them, the cover had the photograph. They had the cover out. You’ve never seen such a beautiful prize. It doesn’t take much. We’re not talking about billions. But where we are, on the ground, where the kids are, what can we do?

About Frances Hesselbein

In the early 1960s, Frances Hesselbein volunteered as the leader of a local Girl Scout troop near Johnstown, Pennsylvania, even though she had no daughters. Her volunteer work with that troop began a long and distinguished association with the Girl Scouts, where she developed a leadership style and organizational model heavily influenced by the writings of Peter Drucker.

Hesselbein served as CEO of the Girl Scouts of the United States of America (1976–90), where she transformed the scouts from a traditional to a modern organization. She worked closely with Peter Drucker in effecting that transformation. Upon retiring from the Girl Scouts in 1990, she became founding president and CEO of the Peter F. Drucker Foundation for Non-Profit Management (later the Leader to Leader Institute). She served as chair of the board of the Leader to Leader Institute until 2010.

Hesselbein has received numerous honors and awards related to leadership, including the Presidential Medal of Freedom (1998). She is an International Leadership Association Lifetime Achievement Award winner.

Explore the complete oral history of Frances HesselbeinBorn or Made?

“I would say, to put it differently, leadership cannot be taught, but it can be learned.”